Park History

The Early Days and Beyond

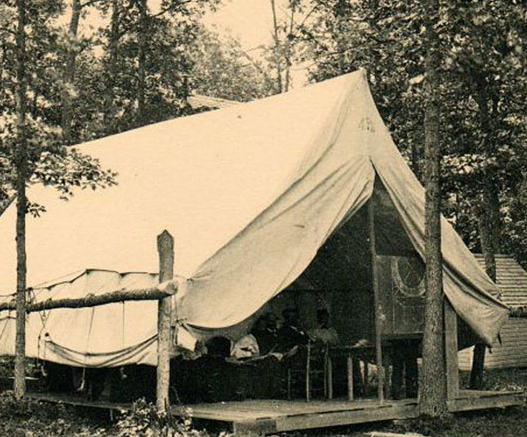

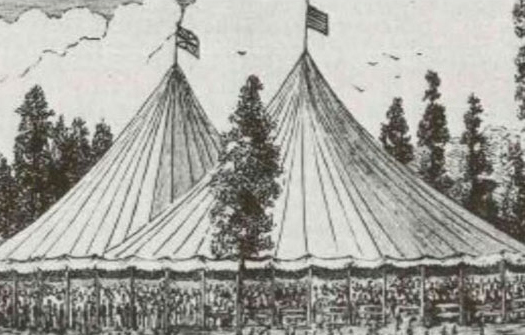

Over a century ago, in 1875, the Thousand Island Park Camp Meeting Association was founded by the Rev. John Ferdinand Dayan. Caught up in the religious revival movement of the time, Rev. Dayan dreamed of a Methodist summer camp where families could enjoy both spiritual and physical renewal. The Camp (forerunner of today’s Thousand Island Park) was non-sectarian, but its activities embraced religious thought and an inflexible observance of the rules of the Sabbath. Since idle minds were “the devil’s workshop,” revival meetings, sermons and public services were in abundance.

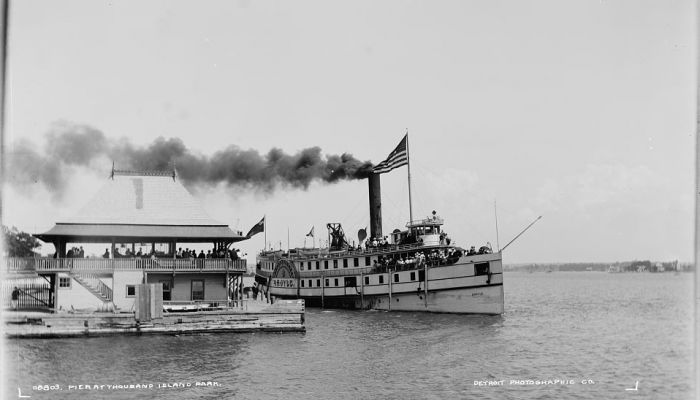

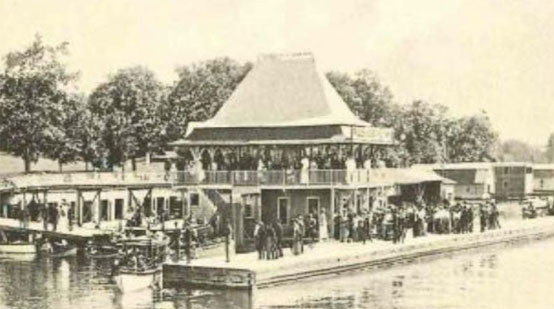

The Camp was an immediate success. Within a year of the first “sale” of lot leases on June 9, 1875, families were summering in their tents or newly built cottages, actively participating in all the Camp had to offer. Arriving daily (but never on Sunday) with their trunks, they found here most of the conveniences of city living…without its vices.

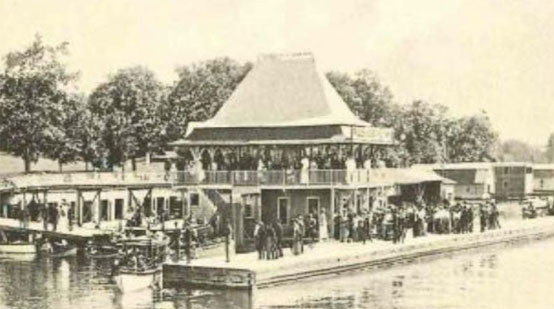

The Camp developed quickly, as did the entire Thousand Islands Region. Attracted by the Camp’s speakers and meetings, as well as its location, would-be vacationers lobbied the Association to provide more accommodations than those to be found in the few rooming houses and tent sites available. In 1883 the Association Trustees announced the grand opening of the Thousand Island Park Hotel. This decision marked the beginning of a temporary trend away from the family-oriented Camp meeting ground toward a more cosmopolitan Park. By 1894, in addition to the public accommodations, there were some 500 to 600 cottages on the Park.

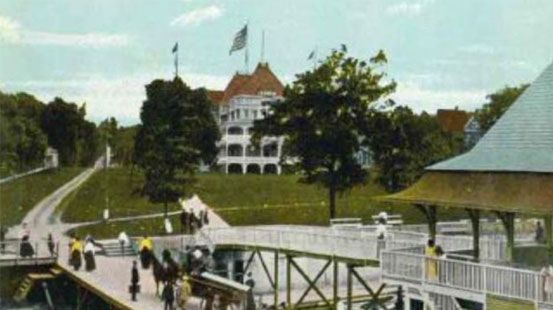

At the turn of the century, the Park was a dynamic summer community which boasted, among other things, a library, yacht club, golf course, roque courts, annual tennis tournaments, daily concerts, an art school, its own printer, a needlecraft shop, fishing guides and boats, a book shop, a photographer…and Sunday services. This was the height of resort life. There was the grand Columbian Hotel, the Wellesley Hotel (which still exists today), and other “hotels” such as the Geneva, the Pratt House and the Rochester which were actually made up of various cottages, each with a separate function. Slowly, the religious emphasis decreased, but the Trustees and Community were secure, surviving and thriving with change.

Fire—always a major threat to the wooden resort—struck several times over the years, generally with reconstruction occurring immediately. The first major fire hit in 1890, burning down the Thousand Island Park Hotel and taking with it many cottages and commercial buildings. The “Iron Cottage” still stands as the bulwark of the east side of Coast Avenue.

In the wake of those flames, the more splendid Columbian Hotel opened in 1892 and as growth continued, the Wellesley Hotel opened in 1903. The largest fire took place in 1912, razing the Columbian Hotel and many cottages to the north and east of today’s “Commons.” Rebuilding commenced again, but times had by then changed. Facing a new reality, the Trustees did not rebuild the hotel. The community began the return to its past as a family resort. Homes were rebuilt, the Playground and Recreation Association was founded, films were brought in for entertainment, and the ban on Sunday docking was lifted.

“Modern Times” had arrived; with them, our way of life had changed. Caught by economic depression and war, the Park contracted. Those cottage owners who could survive the economic and social hardships of the thirties and forties clung to the Park. Yet many could not. The Wellesley Hotel closed and by the mid-1950s, only 320 cottages remained. Except for its loyal families, the charm and tranquility of the Park was lost to the rest of us. Large areas of the Park were seemingly abandoned to time and the elements…yet, quietly, rebirth was underway.

Twenty years later, in 1975, the Park’s Centennial celebration was one of renewed strength. Cottages had been spruced up; the Park’s architectural charm and setting was once again appreciated. Newcomers soon realized what its residents and vacationers already knew: that here was the community that had, through perseverance, escaped the stress of today’s world. Rev. Dayan had indeed prevailed. Here, on the rocking chairs on the porches—porches that seem to be in close proximity—we suddenly realize that individualism and isolation are not synonymous…that a sense of community is as important today as it was in 1875.